‘Kodak is not a foreign name or word; it was constructed by me to serve a definite purpose. It has the following merits as a trade-mark word: First. It is short. Second. It is not capable of mispronunciation.

Third. It does not resemble anything in the art and cannot be associated with anything in the art except the Kodak.‘Some years later he clarified the matter further in a letter to Professor John Manley, of Chicago University: ‘It was a purely arbitrary combination of letters, not derived in whole or part from any existing word, arrived at after considerable search for a word that would answer all requirements for a trade-mark name. The principal of these were that it must be short; incapable of being misspelled so as to destroy its identity; must have a vigorous and distinctive personality; and must meet the requirements of the various foreign trade-mark laws, the English being the one most difficult to satisfy owing to the very narrow interpretation that was being given to their laws at the time.’Now, the English may have been guilty of placing a narrow interpretation upon their patent laws, but this was not the case regarding their views on the etymology of ‘Kodak.’ Despite Eastman’s openness about its mundane origins, alternative theories abounded. The following letters appeared in Amateur Photographer during the latter half of 1896: Odds and Ends (editorial) 7th August 1896, p.112

The Eastman Company can certainly say with truth that they have added a new word to the English language. To many people, “Kodak” is the generic term for any kind of hand-camera, and shopkeepers are often asked for one in this sense. The new papers often use the word as a verb, and speak of people going “to Kodak” places, as readily as the term were to be found in Johnson or Webster.* It was indeed a happy thought to invent outright a new combination of letters; one without any worrying Latin, Greek, or other derivative. That it has been good for its originators goes without saying, and we have no kind of doubt that the actual value of the trademark, “Kodak,” would run into five figures. But the future lexicographer will certainly be puzzled over this word, which has had no forefathers, although he will probably soon find for the orphan a Sanscrit, or possibly a Chinese word which seems to bear sufficient likeness to it to claim relationship.

******************************************************

‘Kodak’ is in fact still found as a verb in Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (1961) and the OED traces the first use as a verb to 1891, but the columnist was correct about the attraction people would feel in finding parallels for the word elsewhere. Over the next couple of months, Amateur Photographer became Amateur Lexicographer, beginning with these two letters on 14 August 1896, p.129:

Sir,

Your remarks in the Amateur Photographer on the origins of the word Kodak made me wonder if it could not be found in Hebrew. Now קָדַח in that language means to burn, whence be bright or brilliant. Kahdak is pretty near Kodak, and Kodaks have had, it seems, a brilliant career. It is quite possible therefore to imagine the Eastman Company, as being true wise men from the East, putting a strange word on the market, and depending on the merits of the camera, turning the word Kodak into a valuable – as you point out – trademark. To others may it not be said “Go thou and do likewise.”

Yours, etc.,

Allan Bayne

Sir,

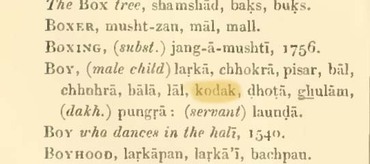

The writer of Odds and Ends in your journal of 7th Aug., seems puzzled over the origins of the word “Kodak.” This word, common in the Hindostanee language, means a youth or boy. It is derived from the Persian. It is spelt exactly like we do, but the “a” is pronounced like “u” in duck. Thus, here is another instance of there being nothing new under the sun. Other oriental words have been anglicised in the same manner in connection with trade purposes.

Yours, etc.,

W.J.F.

W.J.F. was quite right about ‘kodak’, as shown in this excerpt from the fourth edition of John Shakespear’s Dictionary of Hindustani and English (London, 1849.) It is fairly likely that ‘W.J.F.’, whatever his interest in photography, had spent time in India under the British Raj: the word for ‘boy’ or ‘lad’ would have been familiar to any colonial administrator or military officer.

The background to Mr Bayne’s knowledge of Hebrew can only be guessed at, although his quoting from the Gospel of St Luke indicates he knew his Bible; possibly he had learnt some Hebrew to help his reading of the Old Testament. His argument linking קָדַח to ‘kodak’ is somewhat far-fetched, however. קָדַח would be transliterated as qadach, and pronounced more like ‘kaw-dach’, lacking Eastman’s click-click ‘k’ sound. Not to be outdone, Mr Bayne returned to the discussion on 28th August p.169. It is at this point that both his pen and his train of thought began to run rather too fast:

The Hindostanee word “Kodak,” mentioned by W.J.F., is perhaps found in our own language – in English in the word “kiddy,” and in Scotch, “cuddy” (ass). Cuddy ass = once perhaps to boy ass, is prevalent in Scotland. It is quite possible the Hebrew קָדַח to burn = French, chaud i.e. in English, hot. The verb,”kid,” meaning to show, discover, allied to the German kunde (not a bad word for a camera), meaning knowledge, news etc., is just the first part of kodak.

Webster is dissatisfied with the derivation of “God” from “good.” “God” may be derived from the same word as the French chaud, the letters of both being the same etymologically. Both begin with a guttural and end with a dental.

“Goad” would mean the thorn-like flame as well as [the] feeling it produces.

“Guide” would mean light, giving therefore directing power of light.

“Goat” and “Kodak boy” as above, would mean the active, leaping power of fire.

“God” would then mean light in all its powers.

– I am, etc.Allan BaynePerhaps wisely, W.J.F. declined to respond to Mr Bayne’s ever-evolving theories, and further discussion of the matter was absent from columns of the Amateur Photographer for the next fortnight. Then, on 11th September, Mr Bayne returned to make a few final points of a decidedly spiritual nature. (p.209)Sir,

Ere we depart from the word Kodak, as suggested by your editorial note, the chief word has yet to be spoken. If “God, as we found, may mean light in all its powers (Kodak, God act), test the new meaning in one supreme place. Solomon’s conclusion will then be, light (for “God”) will bring every work into judgment, whether it be good or whether it be evil. As the photographer’s work is all brought to judgment and is worthy of gold, silver, copper and writing, when brought to the light of sun and soul, so it is with the works of every man, woman and child – our works, from a photographic exhibition, a one woman or man exhibition, to the spiritual powers that surround us. “There is nothing secret” – see the 139th Psalm. The unseen writing of the seen is not all, there is also the writing of the unseen. In Eccles. X,20 there is the Hadography (unseen writing) of the thoughts also going on.

“The eye cannot be filled with seeing” all the finest photographs, and photography is not an end in itself. Are not all the care, time, knowledge, experience and guidance required to produce a photograph, but a poor thing in their results, unless they be a picture and only a picture of what is necessary to produce a man and woman worthy of their divine original.

Yours, etc.

Allan Bayne

The Scriptural quotations that Bayne cites in support of his ramblings are apt: Psalm 139 begins ‘Do not revile the king even in your thoughts, or curse the rich in your bedroom, because a bird in the sky may carry your words, and a bird on the wing may report what you say,’ while Ecclesiastes Chap. 10, vs. 20 warns ‘You perceive my thoughts from afar…Before a word is on my tongue you know it completely.’ I remain unsure about what he means by ‘Hadography’, although possibly he is referring to Steganography, a form of unseen writing (from the Greek στεγανός, meaning ‘concealed’ and γραφή. meaning ‘writing.’

I can only imagine how bemused George Eastman would have been.

Tomorrow – Freudian interpretations of ‘You push the button and we do the rest.’

I was certainly amazed at the unnecessary time and effort expended in attempting to find ‘fault” with this word. It has certainly passed the test of time!