Daphne du Maurier’s novel Frenchman’s Creek (1941) was made into a Paramount movie in 1944 and told the story of Lady Dona St Columb (Joan Fontaine, above, in her second Du Maurier film) whose love for a French pirate has her disguising herself as a cabin boy, betting, and wielding a knife, amongst other activities not expected of an aristocratic lady in 17th century Cornwall.

Although the gorgeous colour and lavish costumes of Forever Amber and Frenchman’s Creek make the films very easy on the eye, both of them seem excessively long and not nearly as much fun as they should be. This cannot be said of The Wicked Lady (1945), a film adaptation of Magdalen King-Hall’s The Life and Death of the Wicked Lady Skelton, which had been published earlier that same year. Loosely based on the life of Lady Kathleen Ferrers, it starred Margaret Lockwood as Barbara Skelton, who opens the film by stealing the groom of her best friend Caroline (Patricia Roc) at the altar. (Roc also supported Lockwood in Love Story (1944) and Jassy (1947), slapping her face in all three films.)

Bored with married life as the lady of the manor, Barbara starts dressing as a highwayman and carrying out armed robberies at night. During one such escapade she meets notorious highwayman Jerry Jackson (James Mason), and the two become lovers as well as partners in crime. Inevitably, their exploits catch up with them, Caroline gets her revenge, and the gallows beckon for at least one of the wicked pair…

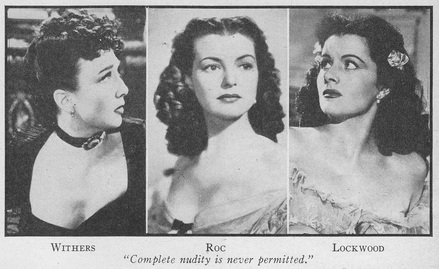

Margaret Lockwood clearly relished the part of Lady Barbara, and audiences loved her performance. Gainsborough melodramas excelled in such bodice-ripping productions, with lavish costumes and Gothic settings. Unfortunately, when the film crossed the Atlantic in 1946, the American censors were upset by what they saw.

Although it had not been a problem in Britain, the low-cut costumes worn by Margaret and Patricia exposed rather too much flesh for American tastes, and in consequence, Lockwood and Roc were called back to Gainsborough Studios at the end of August so that certain scenes (such as the two ladies bouncing along in a coach on their way to Tyburn) could be re-shot from different angles. This was a tedious and costly business, as – to ensure continuity – both actresses had to replicate gestures and expressions, while props needed to be reassembled in precise positions. Decorative frills and ruffles were added to Elizabeth Haffenden’s beautifully-designed costumes to cover up any bare flesh, and one of Lockwood’s dresses had to be borrowed back from Hermione Gingold who was using it a sketch in her satirical revue Sweetest and Lowest at the Ambassadors Theatre. Gainsborough resented the tiresome and costly fuss, but it succeeded in generating a great deal of publicity that gave the film a new lease of life at the box office.

The studio, of course, needed to accept the distributors’ demands in order to have The Wicked Lady shown in the U.S.A. In outlining the nature of the problem, officials at the MPAA devised a new word, ‘cleavage’, which replaced the old-fashioned ‘décolletage.’ How they came up this word I do not know; perhaps the answer can be found in original papers held in the MPAA archives? As a youngster I used to wonder why the Bible (in the King James Version with which I grew up) had the line: ‘Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh’ – which suggested two things cleaved together – when everyone knew a meat cleaver cut things in two. I’ve still never really understood that, but the OED defined ‘cleavage’ as ‘The cleft between a woman’s breasts as revealed by a low-cut décolletage,’ and stated that the first use of the word was in an article in Time magazine on 5 August 1946, which I give in full below.

[Note: The ‘Johnston Office’ is a reference to Eric A Johnston (1896-1963) who succeeded Will H Hays in 1945 as president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association. Understandably, one of his first actions was to simply the organisation’s unwieldy title to the Motion Picture Association of America.]

Cleavage & the Code

Time: the weekly news magazine

Vol. XLVIII, No.6 (August 5, 1946) p.98

Which is more sexy – an actress’ half-covered bosoms or her uncovered legs?

British moviemakers, puzzled by U.S. cinemorality, want a serious answer to this question. For the past fortnight, the man who knows all anyone needs to know about U.S. censorship has been in London trying to explain it in simple English. It is a tough job – even for the Johnston Office’s jowly, jolly Joe Breen, No.1 U.S. ‘interpreter’ of the Hollywood morality Code.

The basic fact that amazes the British – the Code is a voluntary brake Hollywood puts on itself. Its clearest purpose: to keep non-Hollywood censors – official and amateur – out of the industry’ hair. (The Code’s dozen-odd pages of printed rules need no explanation. Samples: ‘Adultery…must not be…justified, or presented attractively…Complete nudity is never permitted…)

Wicked Lady, a 1945 picture starring Margaret Lockwood, James Mason and Patricia Roc, was a big moneymaker in England. But the U.S. will have to wait to see it. Low-cut Restoration costumes worn by the Misses Lockwood and Roc display too much ‘cleavage’ (Johnston Office trade term for the shadowed depression dividing an actress’ bosom into two distinct sections). The British, who have always considered bare legs more sexy than half-bare breasts, are resentfully reshooting several costly scenes.The picture’s chief moral lapse: it makes adultery look like too much fun. At the end of all his wenching, the rake dies as he has lived – happy and unrepentant. Death is not just what he deserves, but the Johnston Office wants him to show some remorse too.

Pink String and Sealing Wax stars Googie Withers, who was none too careful about that cleavage. The Hollywood Codists – who convinced themselves that Hollywood’s Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice were morally clean – have raised eyebrows over the picture’s theme: premeditated murder.

Bedalia allows Margaret Lockwood to poison three husbands for their insurance and then commit suicide when her fourth begins to get the idea. Suicide, in the U.S. is a sloppy out for wrongdoers. A tidy U.S. ending will hand the murderess over to the cops.

In London, last week, Interpreter Joe Breen’s good humor was holding up. ‘The difference between me and most people in Hollywood,’ he said, ‘is that I know I am a pain in the neck.’ But the British press – ignoring the fact that British movie men had invited him over – attacked him as a bluenose. The New Statesman and Nation complained:

…America’s artistes many strip

The haunch, the paunch, the thigh, the hip,

And never shake the censorship,

While Britain, straining every nerve

To amplify the export curve,

Strict circumspection must observe…

And why should censors sourly gape

At outworks of the lady’s shape

Which from her fichu may escape?

Our censors keep our films as clean

As any whistle ever seen.

So what is biting Mr. Breen?

************

Pingback: Belgrave’s Books | Special Collections